Main content blocks

Contur secțiune

-

Prezentul curs este destinat studenților anului I, frecvență redusă cu un nivel pre-intermediar și intermediar de cunoaștere a limbii engleze și care necesită să-și dezvolte competențele lingvistice în domeniul specific viitoarei profesii. Studierea acestui limbaj îmbogăţeşte vocabularul şi dezvoltă deprinderea de a discuta pe teme strîns legate de specializarea studenţilor.

Prezentul curs este destinat studenților anului I, frecvență redusă cu un nivel pre-intermediar și intermediar de cunoaștere a limbii engleze și care necesită să-și dezvolte competențele lingvistice în domeniul specific viitoarei profesii. Studierea acestui limbaj îmbogăţeşte vocabularul şi dezvoltă deprinderea de a discuta pe teme strîns legate de specializarea studenţilor.Prin urmare, cursul se axează pe studiul mai aprofundat al terminologiei juridice cu scopul de a ajuta studenţii să obţină un set specific de competenţe-cheie necesare pentru formarea specialistului in domeniul juridic.

De asemenea, cursul propune o gamă largă de teme de specialitate oferindu-le astfel studenţilor posibilitatea de a obţine deprinderi de lucru cu limbajul specializat.

-

În vederea eficientizării procesului didactic, în perioada sesiunii instruirii, orele practice de limbă engleză se organizează pe această platformă. Vă rugăm să vă atârnați destul de serious și să participați activ la toate sarcinile propuse.

Vă mulțumim.

-

Warning

Before submitting the test, check the following:

- Punctuation and capitalization (Remeber: Capital letters are only used at the beginning of a sentence. If you have to give the correct term or collocation for the provided definition, use minuscules.)

- Spelling (Any mistake in writing the word will be considered a mistake, e.g. if you write ground instead of grounds, that is definitely wrong as they have completely different meanings.)

- Spaces (Do not add any unnecessary spaces as the platform considers it a mistake. The same is true with blending, i.e. when there is no space between words where it should normally be, e.g. He is arenown writer. - wrong - He is a renown writer. - right)

Such mistakes would cost you valuable points.

-

-

This topic focuses on people who have made a significant contribution to the development of the law, from judges and legislators to writers on importanat legal topics.

-

-

- you will learn about Lord Lenning, an influential judge, who has significanty contributed to the development of English law;

- you will learn about the judicial precedent and how it operates within the court hierarchy of the English legal system.

-

-

Latin words and expressions are still relatively common in the legal profession. How many of the meanings can you match with the expressions?

-

This activity has the aim to enlarge your specialism vocabulary with 10 additional terms. Read them carefully and then you have 3 attempts to correctly match the definitions with their corresponding terms.

-

You have 10 minutes to read the following text and to remember as much as you can about the given personalities and their contributions to the development of the law. Below the text you have a Reading Comprehension activity which will check your understanding and memory. You will have just 10 minutes to do it, therefore read the information carefully.

People Who Have Had A Great Influence On The Development Of The Law

Person Achievement Effect Alfred the Great introduced the idea that all crimes were an offence against the king crimes are still prosecuted by the government not by private citizens Sir William Blackstone

wrote the Commentaries on the Laws of England important foundation of both US and English law Napoleon Bonaparte was the Emperor when the French Civil Code was written brought into law the ideals of the French revolution Cicero member of the Roman Senate who wrote about the principles of justice established the idea of rights and duties in natural law Sir Edward Coke champion of the common law; wrote Coke's law reports challenged the arbitrary power of the monarch Clarence Darrow defended trade union leaders in the United States helped to establish the right to form a trade union under US law Lord Denning an English 20th century judge responsible for finding ways to avoid the rigidity of the common law many of his judgments have now become part of statute law Draco was responsible for the first written laws in Greece introduced state justice rather than private justice Thomas Jefferson author of the US Declaration of Independence in 1776 introduced legal reforms on taxation to provide free education Justinian codified Roman Law in Corpus Juris Civilis his work inspired the modern concept of justice http://www.duhaime.org/LawMuseum/LawArticle-46/The-Laws-Hall-of-Fame.aspx

-

The following 20 questions have the aim to help you remember as much as possible about these outstanding personalities.

-

Read only the 7 topic sentences of the given text below. They are all in bold. Try to guess the kind of information each paragraph will develop. Take notes if you need. Now read carefully the text. Were you right?

The Judicial Achievements of Lord Denning

Alfred Thompson, Lord Denning was one of the greatest judges working in the English legal system during the 20th century. Many of his judicial decisions have had a wide impact on many aspects of the law. He became famous for his landmark judgments. He established the principle of equitable estoppel and ensured that the small print on the back of a ticket could not be used by companies to avoid their legal obligations.

Denning also made some controversial judgments that some jurists believe damaged his reputation. Despite strong evidence in their favour, he did not allow an appeal by a group of Irish republicans, known as the Birmingham Six, against their conviction on terrorism charges, on the grounds that, to do so, would indicate the police investigating the crime had been corrupt. The police had, in fact, interfered with the evidence and after a long campaign the men were eventually released. They had been wrongfully imprisoned for more than ten years.

As Master of the Rolls, the most senior judge in the Civil Division of the Court of Appeal, Denning challenged the principle of stare decisis (judicial binding precedent). He believed that if a rule had been made by the Court of Appeal, it could also be changed by it. In the well-known case of Spartan Steel and Alloys Ltd v Martin and Co [1972) 3 All ER 557, CA Denning did not follow precedent and based his judgment on a thorough analysis of the facts of the case.

In Central London Property Trust Ltd v High Trees House Ltd [1947] KB 130 Denning appeared to dispute the concept that in a contract there must be consideration. The facts of the case were that the plaintiffs rented out their property, a block of flats in central London, to the defendants at a fixed rent agreed by both parties. After this agreement was made, World War II started and the defendants found it difficult to find tenants for the flats. The plaintiffs promised to cut the annual rent by half. After the war ended, the flats again became fully occupied and the plaintiffs wanted to receive the original rent. The court decided that they were entitled to the full rent but starting only from the end of the war. Denning argued that the plaintiffs’ promise to reduce the rent stopped them from enforcing the original contract, even though the defendants had not given any consideration. This promise estopped, or prevented, the plaintiffs from enforcing their strict legal rights.

Denning adopted his famous common-sense approach in Thornton v Shoe Lane Parking [1971] 1 All ER 686, CA. The plaintiff bought a ticket to park his car in the defendants’ car park. The ticket was issued subject to the conditions displayed on a notice in the car park. These conditions, in very small print, stated that the owners of the car park were not liable for any injuries caused to their customers. The plaintiff was injured, partly as a result of the defendants’ negligence. The court held that the plaintiff was not bound by the conditions. Denning stated that: ‘In order to give sufficient notice, it would need to be printed in red ink with a red hand pointing to it.’ The defendants could not avoid their duty of care unless they informed their customers about the conditions for parking in a clear and appropriate way.

Denning’s judgments were written in clear and comprehensible English. They were very different from the legalistic language used by many of his fellow judges. The reasons for his decisions could be understood by people who were not lawyers. One of his most famous judgments was in Miller v Jackson [1977] QB 966, CA in what became known as ‘the cricket case’. This involved the traditional English summer sport. A family that had just bought a house next to a cricket ground complained that cricket balls were being hit into their garden and disturbing their right to its peaceful enjoyment. Denning began in the following way:

In summertime village cricket is the delight of everyone. Nearly every village has its own cricket field where young men play and old men watch. In the village of Linz in County Durham [in the north of England], they have their own ground where they have played these last 70 years ... yet now after these 70 years a Judge of the High Court has ordered they must not play there anymore.

Despite the simplicity of his language, the ideas and concepts he expressed were often extremely complex and challenged the rigidity imposed by the common law. Although some of his decisions were overturned by the House of Lords, many of the causes he championed were written into statutes. Examples of these are the right of deserted wives to remain in the marital home, and the concept that a person who makes a negligent misstatement cannot later rely on it.

Vocabulary Notes:

1. Estoppel

A rule of law that when person A, by act or words, gives person B reason to believe a certain set of facts upon which person B takes action, person A cannot later, to his (or her) benefit, deny those facts or say that his (or her) earlier act was improper.

A bar to a party from asserting a legal claim or defense that is contrary or inconsistent with his or her prior action of conduct.

A promise made to another party to a contract that the contract will not be enforced in whole or in part and which, once acted upon, prevents subsequent proceedings to enforce the contract as against the person who relied on the promise.

NB: Equitable estoppel is a doctrine where a person is prevented (estopped) from insisting on what would otherwise be legal rights if it would be unfair (inequitable) to do so. It is sometimes known as promissory estoppel because it may occur when a person promises to do something or not to do something which may originally have been a term of the contract and then goes back on his word.

As Lord Denning MR put it in Moorgate Mercantile v Twitchings [1976] 1 QB 225 at 241: ‘It comes to this: when a man, by his words or conduct, has led another to believe in a particular state of affairs he will not be allowed to go back on it when it would be unjust or inequitable for him to do so’

4. Precedent

A case which establishes legal principles to a certain set of facts, coming to a certain conclusion, and which is to be followed from that point on when similar or identical facts are before a court.

Latin: stay with what has been decided, the principle of judicial binding precedent.

6. Statutes

The written laws approved by legislatures, parliaments or elected or appointed houses of assembly.

-

This quiz will test your understanding of the text and of the kind of information the paragraph's topic sentences develop.

-

Read the following text.

Judicial Precedent

Judicial PrecedentJudicial precedent can be defined as the principle whereby judges are required to follow the decisions made in previous cases which have sufficient similarity. Cases decided by lower courts must always follow the precedent set by higher courts. The aim of stare decisis (Latin for ‘the decision must stand’) is to provide consistency and predictability in the decision-making process of various courts.

The judgment may fall into two parts: the ratio decidendi (the reason for the decision) and the obiter dictum (something said by the way). The ratio decidendi always applies to the precise facts of the case and is binding. In other words, it sets a precedent that must be followed. The obiter dictum is where a judge speculates on what might have happened if the facts had been different. This part of the judgment is persuasive rather than binding and so does not have to be followed. In the High Trees case, Lord Denning decided that the plaintiffs were entitled to payment of the full rent only after the war had ended. This was the ratio decidendi. He speculated that the plaintiffs would not be entitled to the full rent from the start of the war as they had promised to cut the rent by half to ease the defendants' financial difficulties. However, as this was not based on the strict facts of the case, this part of the decision was obiter dictum.

The court hierarchy dictates the way in which judicial precedent operates. Under section 3(1) of the European Communities Act, the decisions made on matters of European Community Law are binding on all courts within the English legal system, including the Supreme Court. If matters of European Community Law are not involved, the Supreme Court is the highest court in the land. The Supreme Court is bound by its own decisions unless the court decides in a particular case that this is not right. This was laid down by Lord Gardiner in the Practice Statement in 1966. Supreme Court decisions are binding on all lower courts.

The Court of Appeal (Civil Division) must follow the decisions of the Supreme Court even if it is considered wrong to do so. In Young v Bristol Aeroplane Co Ltd [1944] KB 718, CA, the Court of Appeal decided it is also bound by its own decisions except where:

- previous decisions in the Court of Appeal conflict. It must then decide which one to follow.

- a decision of its own conflicts with a Supreme Court decision, even if that decision has not been expressly overruled by the Supreme Court.

- a decision of its own was made per incuriam; in other words, by mistake.

The Court of Appeal (Criminal Division) generally has the same rules of stare decisis as the Civil Division. However, because decisions might affect the liberty of the individual, the rules of precedent are not followed as rigidly. This principle was laid down in R v Taylor [1950] 2KB 368, where it was held that if questions involving the liberty of a subject had either been misapplied or misunderstood, the court should reconsider the decision.

The High Court is bound by decisions of the Supreme Court and the Court of Appeal. It is not bound by previous High Court decisions. However, these are of strong persuasive authority and are usually followed. Decisions of High Court judges are binding in the county courts. Decisions made on points of law by judges in the Crown Court are not binding. They are only of persuasive authority, so other Crown Court judges need not follow them. The decisions of the county courts and the magistrates' courts are not binding.

Courts can avoid following a binding precedent in a case by using a legal device called ‘distinguishing’. Cases can be distinguished on either the facts or the points of law. In a case involving a joint enterprise, where two people take part in a robbery, and in the course of the robbery one of the people kills the person they are stealing from, the person who does not actually do the killing may still be liable if he could foresee that this action was likely to follow. If someone is armed with a gun, murder is more foreseeable than if someone is armed only with a stick. In R v Powell (Anthony) and English [1999] 1 AC 1, HL, Lord Hutton made this distinction.

Judicial precedent provides stability and consistency within the legal system. However, there are cases where its rigidity has led to injustices. The arguments are whether these injustices should be rectified by Parliament through a change in the law, or whether it is up to judges to use their skills to avoid a precedent where it would, in the circumstances of the case, be unjust to follow it.

-

This quiz will test your understanding of the text and of the kind of information the paragraph's topic sentences develop.

-

-

This unit focuses on the court systems in more detail and outlines where different types of cases such as torts and crimes are most likely to be tried. By the end of this unit you should be able to:

-

-

- know the different types of courts;

- know how the court systems are structured in the United Kingdom and the United States of America;

- know the basic court orders and injunctions;

- explain the difference between tort and crime;

- know the various types of tort;

- know the basic crime categories;

- distinguish between torts and crimes.

-

-

Types of Courts

1. Small claims court /ˌsmɔːl ˈkleɪmz ˌkɔːt/ - A court that deals with disputes over small amounts of money.

E.g. They were of the view that such debts could be handled perfectly adequately through the small claims court in the first instance.

2. Court of Appeal (also called an Appeal Court / appellate court/ court of appeals/ appeals court) /kɔːt əv əˈpiːl/ - A civil or criminal court to which a person may go to ask for an award or sentence to be changed.

E.g. I think it would be much better to adopt the line of an international court of appeal.

3. Court-martial (n/v) /ˌkɔːt ˈmɑː.ʃəl/ - A court which tries someone serving in the armed forces for offences against military discipline.

E.g. I hardly think if somebody is acquitted he would elect to be tried by court-martial. She is likely to be court-martialled for disobeying her commanding officer.

4. County Court /ˌkaʊn. ti ˈkɔːt/ - One of the types of court in England and Wales and some parts of the USA which hears local civil cases. (There are about 270 County Courts in England and Wales. They are presided over by either district judges or circuit judges. They deal mainly with claims regarding money, but also deal with family matters, bankruptcies and claims concerning land).

E.g. I appreciate the arguments in favour of sending these cases to the county court.

5. The European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) /ðəˌjʊə. rəˈpiː.ən ˌkɔːt əv ˌhjuː.mən ˈraɪts/ also known as Strasbourg Court is a court which considers the rights of citizens of states which are parties to the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights.

E.g. ECHR is taking a number of exceptional measures to respond to the unprecedented global health crisis, having regard to the recent decisions of the French authorities and the Council of Europe.

6. Employment tribunal /ɪmˈplɔɪ.mənt /traɪˈbjuː.nəl/ - A body responsible for hearing work-related complaints as specified by statute. (Formally, it is known as an industrial tribunal. The panel hearing each case consists of a legally qualified chairperson and two independent lay (= not legally qualified) people who have experience of employment issues. Decisions need to be enforced by a separate application to the court. Appeals are made to an Employment Appeal Tribunal)

E.g. Claims must be submitted to an employment tribunal within three month of the alleged act of discrimination.

7. Magistrates' court /ˈmædʒ.ɪ.streɪts ˌkɔːt/ - A court which hears cases of petty crime, adoption, affiliation, maintenance and violence in the home (= domestic violence), and which can also commit someone for trial or sentencing in a Crown Court.

E.g. The case was heard in a magistrates’ court.

8. Coroner's court /ˈkɒr.ə.nərz kɔːt/ - A court presided over by a public official (usually a doctor or lawyer) who investigates sudden, unexpected and violent deaths. (An investigation in a coroner's court is called a coroner's inquest. A coroner's inquest also decides what happens when treasure or something valuable that has been secretly hidden or lost is suddenly rediscovered).

E.g. The Coroner's Court is responsible to inquire into the causes and circumstances of some deaths.

9. Crown Court /ˌkraʊn ˈkɔːt/ - A court above the level of a magistrates' court which hears serious criminal cases, by a judge and a jury in the UK.

E.g. Crown Courts have power to deal with indictable offences, and also hear most appeals from magistrates’ courts.

10. Lands Tribunal /lændz traɪˈbjuː.nəl/ - A court which deals with compensation claims relating to land.

E.g. The Lands Tribunal resolves a range of disputes about the value of land and buildings, and about their occupation, use or development.

11. Commercial Court /kəˈmɜː.ʃəl ˌkɔːt/ - A court in the Queen's Bench Division (= one of the main divisions of the High Court) which hears cases relating to business disputes.

E.g. A commercial court judge ruled the company was wrong to terminate the contract.

12. Rent tribunal /rent traɪˈbjuː.nəl/ - A court which adjudicates in disputes about money paid or services provided in return for borrowing something – usually buildings or land.

E.g. The Rent Tribunal will need a copy of your tenancy contract (mandatory).

13. The High Court /ˌhaɪ ˈkɔːt/ - The main civil court in England and Wales. This is usually the highest court in jurisdiction, the court of last resort.

E.g. The financier could be more than £1m poorer after losing his High Court battle with his former company.

14. The European Court of Justice /ðəˌjʊə. rəˈpiː.ən ˌkɔːt əv dʒʌs.tɪs / - An organization of the European Union, formed of one judge from each member country, that decides on the laws that all its members should follow. It has the power to change decisions made by national courts. (ECJ – short form. It is also called the Court of Justice of the European Communities).

E.g. The ECJ set up to see that the principles of law as laid out in the Treaty of Rome are observed and applied correctly in the European Union.

15. Court of Protection /ˌkɔːt əv prəˈtek.ʃən/ - A court appointed to serve the interests of people who are not capable of dealing with their own affairs, such as patients who are mentally ill.

E.g. The Court of Protection in English law is a superior court of record created under the Mental Capacity Act 2005.

16. The Admiralty Court /ˈædmərəlti ˌkɔːt/ / - The court which is part of the Queen's Bench Division, which decides in disputes involving ships.

E.g. Historically, admiralty courts were a separate part of the court system.

17. The House of Lords /ˌhaʊs əv ˈlɔːdz/ - The highest court of appeal in the United Kingdom. Since 2009, it is known as the Supreme Court. (although appellants unhappy with a decision made here can appeal to the European Court of Justice).

E.g. The House of Lords is the United Kingdom's supreme court of appeal.

18. Juvenile court /ˈdʒuː.vən.aɪlˌkɔːt/ - A court where a person under the age of 18 would be tried.

E.g. The object of that requirement is to make sure that the local authority will put all its views and information before the juvenile court.

19. Lower court /ˈləʊ. ər kɔːt/ - A court of primary jurisdiction, where a case is heard for the first time and whose decisions can be appealed to a higher court.

E.g. The lower court found that evidence was circumstantial.

20. Moot court /muːt/ kɔːt/ - a mock court in which hypothetical cases are argued, usually as an academic exercise for law students.

E.g.The practical training for students is organized at courts of law, and local and international moot court competitions.

Remember:

A courthouse is the general word for a building in which trials take place.

-

This activity checks your understanding of the types of courts and the ability to decide which of the courts is most likely to deal with certain situations.

-

The Structure of the Courts in the UK The UK court system is complicated and – in places – confusing, because it has developed over 1,000 years rather than being designed from scratch.

Different types of case are dealt with in specific courts: for example, all criminal cases will start in the magistrates’ court, but the more serious criminal matters are committed (or sent) to the Crown Court. Appeals from the Crown Court will go to the High Court, and potentially to the Court of Appeal or even the Supreme Court.

Civil cases will sometimes be dealt with by magistrates, but may well go to a county court. Again, appeals will go to the High Court and then to the Court of Appeal – although to different divisions of those courts.

The tribunals system has its own structure for dealing with cases and appeals, but decisions from different chambers of the Upper Tribunal, and the Employment Appeals Tribunal, may also go to the Court of Appeal.

The courts structure covers England and Wales; the tribunals system covers England, Wales, and in some cases Northern Ireland and Scotland.

https://www.judiciary.uk/about-the-judiciary/the-justice-system/court-structure/

-

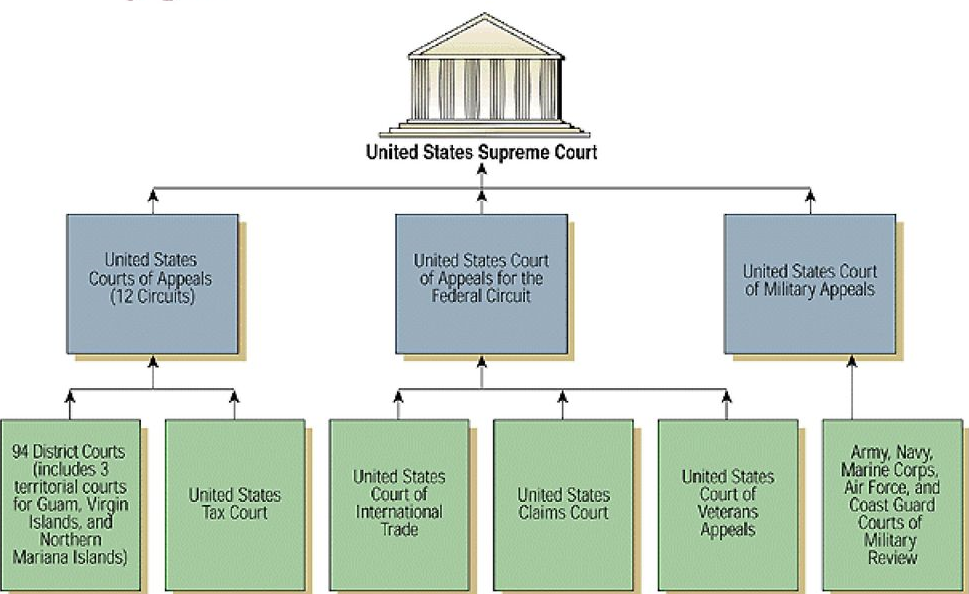

The American Court System

The United States has a unique court system in that it is divided between a federal system covering the whole country and independent systems in each state and US territory. The systems can cover the same grounds in criminal, civil and administrative law. For instance, there are both federal and state laws against murder, lawsuits can be brought by the same people against the same people in both state and federal court and both the federal and state government regulate things like securities and the environment. The running of these two parallel systems simultaneously on the state and federal levels is known as “federalism.”

The federal court system was established by Article 3 of the Constitution, but new judges and courts are established by Congress and the President. State court systems are established by state law or state constitution.

The details of the structure of the federal court system was the first order of business of the first US Congress, which passed the Judiciary Act of 1789 as Senate Bill 1. That Act created the federal judiciary system still in use today. The original federal judicial system consisted of a Supreme Court with six Justices, three appeals courts, each presided over by two Supreme Court justices and a district court judge and 13 trial courts, each presided over by a district judge.

Over the years, the numbers of courts and judges have changed with the growth and shifting of populations. Today, the federal judicial system consists of the Supreme Court with nine justices, thirteen circuit courts of appeal (11 geographic circuit courts, the D.C. Circuit court and the Federal Circuit) and 94 district courts. There are also a number of specialty courts of limited jurisdiction.[3]

The 94 district courts are scattered across the country, with each state and territory having between one and four districts. In districts with large populations, one district court may have offices, courtrooms and judges in multiple locations. For instance, the Northern District of Ohio court has locations in Cleveland, Toledo, Akron and Youngstown.[4] Each federal district also has a bankruptcy court.

Congress also created several “Article I,” or legislative courts, that do not have full judicial power. These include the Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims, the Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces and Tax Court.[5] There are also military courts and tribunals that are not part of the federal court system under Article III.

https://lawshelf.com/videocoursesmoduleview/the-american-court-system-module-1-of-5

-

Injunction /ɪnˈdʒʌŋkʃən/ - an official order given by a law court, usually to stop someone from doing something. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/injunction

Choose the best word to complete the sentence and type it in the space provived. Be careful to spell it correctly, if it is written with a capital letter than you should also use a capital letter .

You can use any of the given links to dictionaries below in case you need:

-

Read the text and complete the blank spaces dragging the appropriate words from the given ones below the text.

-

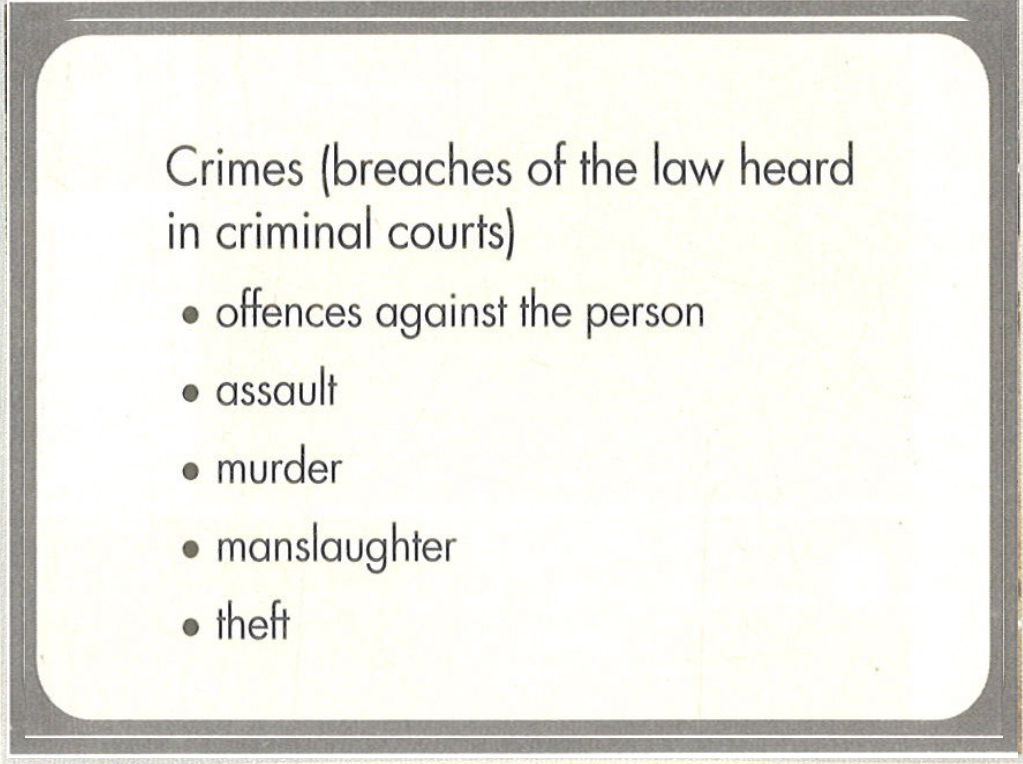

Tort vs Crime

A crime is an illegal act which may result in prosecution and punishment by the state if the accused (the person or people charged with a crime) is / are convicted (found guilty in a court of law). Generally, in order to be convicted of a crime, the accused must be shown to have committed an illegal (unlawful) act with a criminal state of mind.

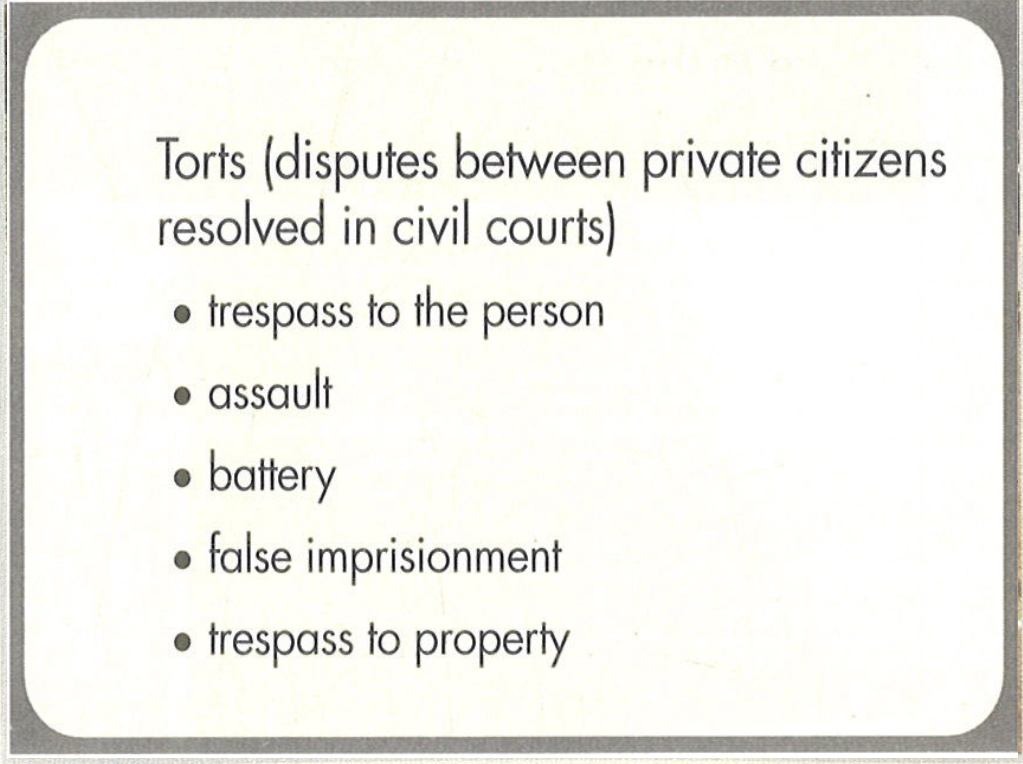

A tort is a civil wrong or wrongful act, whether intentional or accidental, from which injury occurs to another. Torts include all negligence cases as well as intentional wrongs which result in harm.

There are several heads of tort in English law. The most important are:

-

-

- Negligence;

- Trespass to land;

- Nuisance;

- Trespass to the person;

- Defamation.

-

Lawyers usually devide these heads into two categories:

-

-

- torts that cause harm to people, and

- torts that cause harm to land.

-

-

-

Read the following text.

TORTS THAT CAUSE HARM TO PEOPLE - TRESPASS TO THE PERSON

Trespass to the person means to harm someone in a physical way. To make someone afraid that you will physically hurt them is the tort of assault. To actually hurt someone in a physical way is the tort of battery. To keep someone in a certain place without that person's permission is the tort of false imprisonment. All of these torts are known as trespass to the person.

Defamation occurs when someone makes a negative statement about another person which harms that person's reputation. In other words, it means saying or writing something negative about someone, so that other people think in a more negative way about that person.

Defamation comes in two forms:

- The tort of libel that is in fact publishing the statement in a permanent form, for example, writing it in a book.

- The tort of slander which refers to a statement in a form that is not permanent, for example, saying something in ordinary conversation.

Negligence occurs when you cause harm to another person because you were not careful enough. The law of tort says that in situations where you can anticipate that your conduct is likely to cause harm to another person then you have a duty to be careful. Lawyers refer to this duty as the duty of care. Negligence is the most common ground for claimants bringing an action in tort.

-

First, listen twice to this conversation between a lawyer and her client. After that, click Start the quiz now, and do the task. This task asks you to decide if the given statements are true or false.

-

-

-

Language and subject note:

The terms malfeasance, misfeasance, and nonfeasance come from Anglo-Norman and came into the English common law of tort from old French law.

1. Malfeasance means doing something wrong or illegal.

2. Misfeasance means doing something which is legal but in an appropriate way.

3. Nonfeasance means failing to do something that is a legal requirement or professional obligation.

These terms are often used when referring to people acting in a public capacity. An example of malfeasance is where a member of parliament employs someone to look after her children and then knowingly pays her from the secretarial allowance that all Members of Parliament are entitled to.

If the person whom the MP employs to look after the children also does some secretarial work and the MP does not know that paying her out of her secretarial allowance is in breach of parliamentary rules, then this is misfeasance.

If an MP finds out that a parliamentary colleague is paying for a nunny out of her secretarial allowance and then fails to report this breach of rules to the parliamentary select committee, then this is nonfeasance.

4. Assault is an act which intentionally causes another person to expect that unlawful force will be used.

5. Battery is the actual infliction of unlawful force on another person.

6. False imprisonment is unlawfully constraining someone against their will in a particular place.

7. Slander - false and defamatory spoken words tending to harm another’s reputation, business, or means of livelihood. Slander is spoken defamation, “libel” is published.

8. Consent - permission or agreement to do something.

9. Infliction - the cause of harm to another person.

10. To constrain - to control or limit a person's movement.

-

Theft

There are many kinds of theft. You can rob a person with the help of a gun (robbery) or with a pen (fraud). The implication is that one kind is open and clear, the other is hidden. Both educated and uneducated people can be thieves. It is just that they steal different things. The thefts of a rich person can be much bigger and, perhaps, not seen as theft by society.

Thef is not the same as burglary which is only a small part of theft. Theft is not just about (stealing) taking property. It (involves) concerns many other related activities.

So what is theft?

Section 1 (1) of the Theft Act 1968 creates the offence of theft, stating that:

'A person is guilty of theft if he dishonestly appropriates (keeps) property (items) belonging to another with the intention of permanently depriving the other of it (keeping it from the other)'.

The components (elements) of theft are: a. The actus reus (the guity deed) of the (offence) crime. This states that the defendant:

- takes

- one or more items

- owned by another person.

b. The mens rea (the guity mind) which consists of the defendant (accused) acting (behaving):

- dishonestly, and

- meaning to keep the item forever.

A possible defence against a charge of theft is that you (did not know) were not aware the property belonged to another party, or that you intended to (return) give back the property.

Language Note

to rob and to steal are near synonyms, but they are used for different things

- you rob a person or a place, but

- you steal a thing, or money.

People sometimes confuse robbery and burglary

- you rob a bank, but

- you burgle a house.

Synonyms:

- property - items

- belonging to - owned by

- with the intention of - meaning to

- permanently - forever

- to appropriate - to take

-

-

1. Presentations Sarcina

-

2. Glossary Sarcina

-